Professor Louis Compton Miall, Photo by E. E. Unwin

To most current students in Leeds, the name Louis Compton Miall would mean very little. A few might recognise the name from the LC Miall Building, home of the Faculty of Biological Sciences. Our team certainly had never heard of him before we were assigned to create an exhibition on magic lanterns and their relationship with the University of Leeds.

While carrying out research for the exhibition Lighting the Way: Leeds and the ‘Magic’ Lantern, we noticed that Miall’s name kept recurring. It soon became clear that Miall and his pioneering work with magic lanterns have long been overlooked. His innovations were not only crucial to the development of magic lanterns, but to teaching more generally. More on Miall later, first a quick history of the lanterns.

First developed in the 1600s by the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, magic lanterns were an early form of projection equipment, which used a light source and a series of lenses to show images on a much larger scale than ever before. See this previous blog post for a more detailed discussion of the lanterns’ history and workings.

However, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that magic lanterns started to be used widely in education – although in this context they were often called ‘optical lanterns’ instead as ‘magic’ was deemed not serious enough. In a darkened hall, a lecturer would deliver a talk accompanied by slides displayed by a specially-trained ‘lanternist’. This format was used for the rest of the nineteenth century, despite the obvious drawback of teaching in the dark and the difficulty of coordination between the lecturer and lantern-operator.

Magic Lantern in Use During a Biology Lecture

History & Philosophy of Science in 20 Objects. Object 20: Magic Lanterns

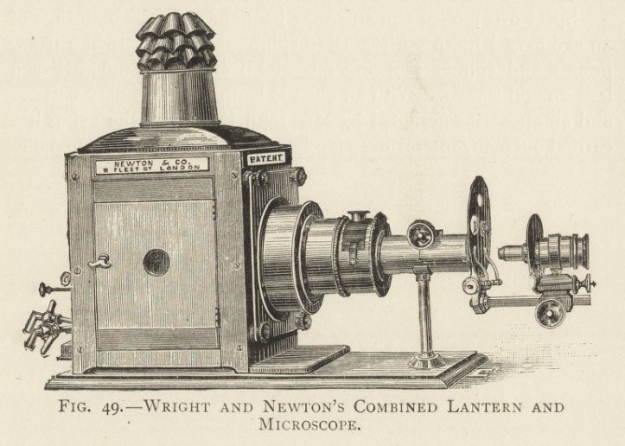

Here, the intervention of Louis Compton Miall was pivotal. He was Professor of Biology at The Yorkshire College and its successor the University of Leeds from 1876 to 1907. In order to display his biological specimens more easily to his students, he developed a more stable and powerful lantern which could broadcast images that were visible even with the lights on. Miall could then combine the lantern with specialist equipment such as microscopes or liquid-containing ‘tank slides’, allowing the live demonstration of experiments to an entire lecture hall.

A Nineteenth-Century Newton and Co. Combined Lantern and Microscope

A. Pringle, The Optical Lantern for Instruction and Amusement (1899)

Professor Miall also altered the set-up of the lantern so it could be operated by the lecturer unaided. He could now seamlessly teach and operate the lantern, without having to interrupt his lectures to communicate to an operator if there were any difficulties. In an article of May 1890 from the Review of Reviews entitled ‘How to Utilise the Magic Lantern; Some Valuable Hints for Teachers’, its author summarises the benefits of Miall’s method:

“The most novel and important points are that the slides are exhibited in a well-lighted room, and all the necessary manipulations are done by the lecturer or teacher without any difficulty.”

Today, in the age of the digital projector, most University staff structure their lectures and seminars around a PowerPoint presentation, which they use to illustrate their points and invite wider discussion. This teaching method, which is so taken for granted today, relies on the innovations of Professor Miall in allowing lecturers to control their own presentations and show them in a lit room.

Without Louis Compton Miall, the whole structure and teaching practices of higher education could thus have been radically different. It is time to recognise Miall’s achievements with magic lanterns at the University of Leeds, and shine a light on this largely unsung educational pioneer.

In the Lighting the Way exhibition, we track the evolution of magic lanterns at the University of Leeds, including highlighting the contributions of individuals such as Professor Miall and other educators to the development of the lanterns’ educational potential. Amongst the objects on display are a lantern produced by the famous Newton & Co. optics; various lenses and accessories used in lecture halls, such as an elbow polariscope; and a small sample of the Museum’s collection of around 5,000 lantern slides, including two mechanical astronomy slides.

Lighting the Way: Leeds and the ‘Magic’ Lantern has been curated by MA Art Gallery and Museum Studies and MA Arts Management and Heritage Studies students in collaboration with the Museum of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine. It will be displayed in the Philosophy, Religion and the History of Science Common Room on the 1st floor of the Michael Sadler Building from 13 December 2018.

More information can be found on the use of magic lanterns in education at Leeds here.