Cupboard of Dead Bugs: Life Lessons from Insects for Economics, Empire and Evolution By Emily Herring

October’s object was well-suited for the month of Halloween. They creep, they crawl, and, in this particular instance, they are very much dead. For the eighteenth lecture in the HPS in 20 Objects public lecture series, PhD students Matt Holmes and Alex Aylward chose to get historical and philosophical about a cupboard of dead bugs. More precisely, a teaching collection belonging to the Museum of HSTM at the University of Leeds. As both speakers demonstrated over the course of the lecture, there is a lot more to be learned from this collection of insect specimen than simply insights into natural history.

Matthew Holmes kicked off the lecture by reminding us of a very important anniversary: 2017 marks the 40th anniversary of the science fiction/horror film Empire of the Ants. The film is very loosely based on a 1905 short story of the same title by H. G. Wells.

Both the film and the short story feature humans being tormented by organised attacks from super-intelligent ants. While the film, which was of the unintentionally-funny-0%-on-rotten-tomatoes kind, had one critic saying “you’ll be rooting for the ants”, Wells’ celebrated short story went beyond science fiction and tapped into late nineteenth century and early twentieth century fears about the viability of Western empires. The characters of the fictional world in Wells’ story, feared that the highly intelligent insects might eventually form cultures of their own and seek to start their own colonies. Around the time Wells published his ant story, more practical fears linked to agriculture and health encouraged the development of methods designed to control insect pests, also known as economic entomology. People like Bradford-born entomologist L. C. Miall started listing these different methods of control or extermination which included the not very effective “swatting the insects away by hand” technique and various kinds of noxious sprays which had the unfortunate side effect of killing not only the insects but everything surrounding them. Another method was the introduction of insect predators such as birds. In 1866 British sparrows were exported to New York in an attempt to deal with troublesome caterpillars.

The birds did not however limit themselves to the caterpillars and ended up eating the very crops they were meant to be protecting from the insect pests. Therefore, in his section of the lecture, Matt showed that beyond studies in systematics and comparative anatomy, the teaching collections, like the one we have at the University of Leeds, and the development of new forms of practical biology, cannot be separated from the history of the formation of, and attempts to maintain, empires.

In the second half of the lecture, conducted by Alex Aylward, insects, in particular social insects, were also portrayed as pests, but of a different kind. Alex was not referring to the terrible picnic etiquette of wasps but rather to the theoretical puzzles posed by wasps and other hymenoptera that have been pestering evolutionary biologists for decades. For instance, the division of labour between different members of a hive or a colony translates into differences in structure and behaviour. The queen is usually large and spends her life reproducing while some of the workers will usually be much smaller and sterile. Darwin himself worried that these differences in structure and behaviour between the different members of the society might undermine his theory of evolution by natural selection. Indeed, how do the sterile members of an insect society pass on their specific characters and behaviours? In addition, natural selection is often represented as gradually increasing the fitness – i.e. the ability for an entity to survive and to produce other entities similar to itself – of the entities it acts upon. The fitness of a sterile worker in a colony would therefore be zero. In many bee species, sterile castes possess a sting which they deploy in protecting the nest – bringing their own life to an end. Hence, they fail in achieving both aspects of fitness – survival and reproduction. How could natural selection have possibly allowed this situation to evolve?

In the 1960s and 1970s attempts to solve these problems involved using the language of economic thinking: costs, benefits, trade-offs, etc. By broadening the notion of fitness to include the reproductive success of others, especially of our close-kin, it might be possible to make sense of the self-sacrificing behaviour of the sterile workers. This was the theory put forth by English evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton in the 1960s. If we think of relatedness in terms of shared genetic material rather than simply in terms of parent-offspring, then it becomes apparent that most individuals share as much genetic material with their offspring as with their siblings. In the case of Hymenoptera, the amount of shared genetic material can actually be higher between siblings than between parent and offspring. Certain self-sacrificing behaviours might therefore actually pay off, in terms of extended fitness, by increasing the reproductive output of a close relative, even if the immediate cost is high. Hamilton expressed this in the form of an equation, known as Hamilton’s law, which states the relationship between relatedness, r, the benefit of a behaviour, B, and cost C, in terms of this broader notion of fitness. Hamilton’s work was famously popularised by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene (1976).

Over the course of this lecture, insects went from being portrayed as agricultural pests to theoretical pests. Over the past few decades they can also be seen as having gone from being associated with a threat to humankind which needs to be contained, to a man-made ecological disaster in the making. Efforts to contain insect pests led to the development, in the twentieth century, of synthetic pesticides which have not only contributed to endangering many insect species but have also had a detrimental effect on human health. Recent studies have shown that the alarming rate at which the flying insect biomass is dropping puts us on track for an “ecological Armageddon”. Some of the insects in the Leeds teaching collection can no longer be found in nature. Alex therefore concluded the lecture by drawing attention to calls from environmentally-minded commentators for cooperation on a grand scale in order to tackle the problems flagged up by these recent alarming studies.

The video of the lecture is below

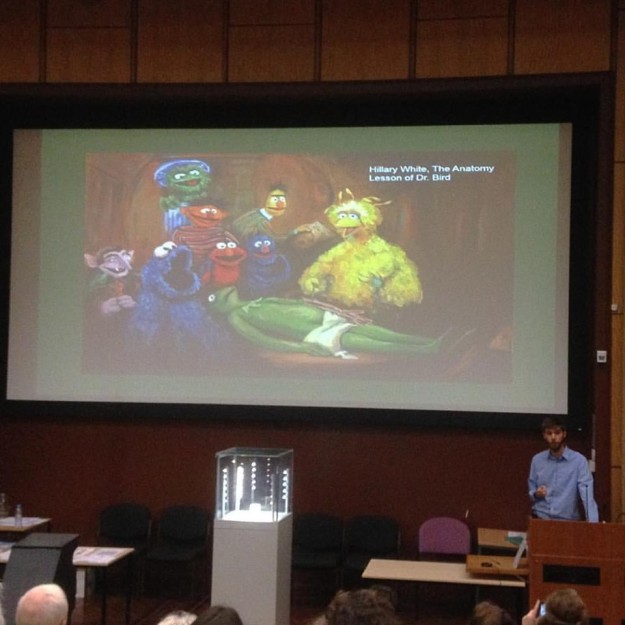

Richard Bellis explains the drawbacks of using cadavers in demonstration; seven of the Sesame Street gang have to crowd around one specimen, as Big Bird orates

Richard Bellis explains the drawbacks of using cadavers in demonstration; seven of the Sesame Street gang have to crowd around one specimen, as Big Bird orates

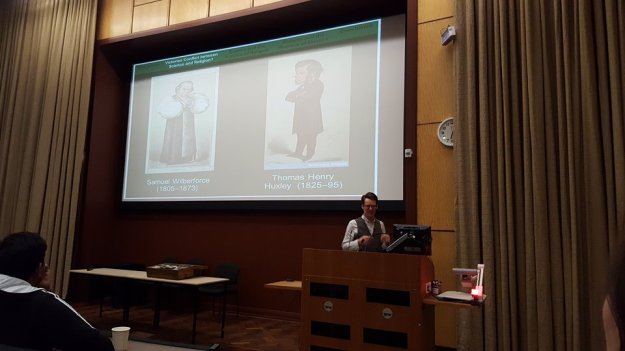

The lecture then moved on to far less-familiar people and more unexpected stories connected with the biblical herbarium, to show how religious belief has long been part of scientific practices, and scientific practices – specifically an interest in natural history and botany – was part of a good Christian lifestyle.

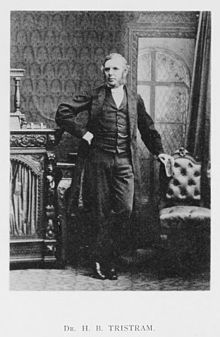

The lecture then moved on to far less-familiar people and more unexpected stories connected with the biblical herbarium, to show how religious belief has long been part of scientific practices, and scientific practices – specifically an interest in natural history and botany – was part of a good Christian lifestyle. Jon then masterfully brought the lecture to its finale, by linking back to the biblical herbarium itself. The author of the pamphlet accompanying the box, Henry Baker Tristram, was a Fellow of the Royal Society but also a clergyman and Church Missionary Society activist. He was, perhaps most surprisingly, the first naturalist to apply Darwin’s theory in print. He embodied how, for many Victorians, the practice of religion and the practice of science were mutually supportive. He later opposed the Darwinians, but largely because of how they behaved, sneering and putting down their opponents, and because natural selection was inadequately supported, rather than because he regarded Darwin’s theory as atheistic.

Jon then masterfully brought the lecture to its finale, by linking back to the biblical herbarium itself. The author of the pamphlet accompanying the box, Henry Baker Tristram, was a Fellow of the Royal Society but also a clergyman and Church Missionary Society activist. He was, perhaps most surprisingly, the first naturalist to apply Darwin’s theory in print. He embodied how, for many Victorians, the practice of religion and the practice of science were mutually supportive. He later opposed the Darwinians, but largely because of how they behaved, sneering and putting down their opponents, and because natural selection was inadequately supported, rather than because he regarded Darwin’s theory as atheistic.